The Crimean Tatar imprisoned by Russia, promoted to high office by Ukraine

28 January 2025

28 January 2025

Kyiv, Ukraine – Seventeen years in jail for “smuggling explosives” and “organising a diversion” to blow up a natural gas pipeline.

That’s the sentence Nariman Dzhelyal, a Crimean Tatar community leader in the annexed Black Sea peninsula, was handed in 2022 after a year-long trial that Ukraine decried as “trumped-up” and orchestrated by the Kremlin.

list 1 of 4

Crimea was never Russian

list 2 of 4

EU must boost defence spending to counter Russia’s threat, says Kallas

list 3 of 4

Could the war between Russia and Ukraine end soon?

list 4 of 4

North Koreans are ‘disciplined’, armed with high-quality ammo, says Ukraine

end of list

Dzhelyal, 44, denied all of the allegations against him. He said he could have been charged with anything from “separatism” to “attempts to undermine Russia’s constitutional order”.

These are the accusations thousands of Kremlin critics and Muslims have faced in Chechnya, Dagestan and other mostly Muslim regions.

But in Dzhelyal’s case, he and other Tatar activists believe the Kremlin chose “diversion” as a possible pretext for wider persecution of activists of the Mejlis, the informal Tatar parliament, and the entire Tatar community.

The Kremlin labelled the Mejlis an “extremist” organisation” in 2016.

“Through my case, there was a possibility – and there’s still one – to proclaim the Mejlis not just an extremist, but a terrorist organisation, and spread harsher persecution to all of its activists,” Dzhelyal told Al Jazeera in the Kyiv office of the Mejlis.

Advertisement

He was released in a prisoner swap in June 2024, arriving in Kyiv to be greeted by his family, dignitaries and reporters.

Had the Mejlis been branded “terrorist”, anyone displaying its insignia – including the tamga, a blue flag with a yellow seal that is ubiquitous among Tatar drivers – would have faced jail.

The tamga dates back to the Muslim dynasty that ruled Crimea as part of Ottoman Turkiye until Russia annexed it in 1783.

However, the Kremlin appears to have opted against widening the crackdown.

Observers say the reasons may vary from pressure from Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to the conflict of interests among Russian law enforcement agencies and political clans.

“There’s no reasonable logic; there are uncoordinated and not-always-compatible interests and views of various agencies,” Kyiv-based rights advocate Vyacheslav Likhachyov told Al Jazeera.

However, Moscow still singles out Tatars, whose community of 250,000 comprises only 12 percent of Crimea’s population.

Out of what rights groups have termed Crimea’s 208 “political” prisoners, they say 125 are Tatars.

Many arrested Tatars await trials for months or even years, and those sentenced to jail on charges ranging from “terrorism” to “discrediting Russia’s military” often end up in distant Siberian prisons.

“People are jailed for nothing. These people didn’t blow up anyone, didn’t kill anyone, did nothing of the kind,” Dzhelyal said.

Tatars once dominated Crimea, but these days, the majority of the peninsula’s population are ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, whose forefathers arrived after the 1944 deportation of the entire Tatar community.

Advertisement

Soviet leader Josef Stalin accused them of “collaboration” with Nazi Germany, but experts say the real reason was Crimea’s geographic and cultural proximity to Turkiye – only 270km (170 miles) across the Black Sea and sharing hundreds of years of history.

The Tatars were deported to Central Asia in cattle cars, with little food or water, and almost half died en route.

“One day won’t be enough, one or two books won’t be enough to tell how they tortured us. When we die, our bones will remember it,” an elderly villager who survived the deportation told this reporter in 2014, just days before the Moscow-organised “referendum” that made Crimea part of Russia.

Dzhelyal’s father, Enver, was six in 1944. His family ended up in the sun-scorched Uzbek city of Navoi, where he would work at a chemical plant and meet Nariman’s mother.

He died in 2022, and Nariman was not allowed to leave jail to attend his funeral.

“Not being able to say farewell wasn’t easy,” Dzhelyal said. “But it was Allah’s will; I perceive it the way a Muslim should.”

The community dreamed of returning to Crimea, but Moscow allowed it only in the late 1980s – without compensation for lost lives and property.

Tatars mostly settled in arid northern Crimea, while locals demonised and ostracised them, and regional authorities did not allow them to hold jobs in law enforcement and administration.

When Moscow flew in thousands of soldiers and organised pro-Russian rallies in Crimea in February 2014, Tatar leaders immediately understood the danger.

Advertisement

They knew how Moscow handled “extremism” in the Muslim-dominated areas in the North Caucasus and the Volga River region.

Dzhelyal recalled a conversation with a Chechen man who pleaded with him not to “let them treat you the way they treated us”.

“They killed as many Chechens as there are Tatars,” the man told him.

The Mejlis chose a Gandhian policy of non-violent resistance.

“Russia was provoking a conflict. They just needed one, because it would justify the presence of the Russian army as ‘peacekeepers’,” Dzhelyal said.

Tatars stayed away from altercations with taciturn Russian servicemen and “self-defence” units that were put together and trained by Russian officers.

Dzhelyal and other Tatar leaders claimed that Moscow specifically brought in Serbian ultra-nationalists who had participated in the 1995 Srebrenica genocide of Muslims.

In March 2014, this reporter saw four armed Serbians patrolling a road in southern Crimea.

The non-violent resistance helped prevent turning Crimea into another Chechnya, where Moscow’s “counter-terrorist operation” morphed into a war, analysts said.

“There is no counter-terrorist operation because the Tatars’ resistance is essentially non-violent. And the religious factor is less” significant than in other Muslim regions of Russia, Maksym Butkevych, a Kyiv-based human rights advocate and serviceman, told Al Jazeera.

However, blood was spilled.

According to activists, a Tatar protester was abducted before the “referendum”, and his tortured body was found with his eyes poked out.

Advertisement

Dozens of Tatars were abducted and are presumed dead. Hundreds have been arrested, or have had their houses searched by armed men who often broke in at dawn, frightening children.

Tatar businessmen face pressure, blackmail and expropriations.

However, Dzhelyal is adamant that “Ukraine is doomed to be independent” from any Russian meddling.

“Sooner or later, we will get some preferences for [Tatars], and it will always displease Moscow,” he said.

On December 20, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy appointed Dzhelyal Ukraine’s ambassador to Turkiye.

Related News

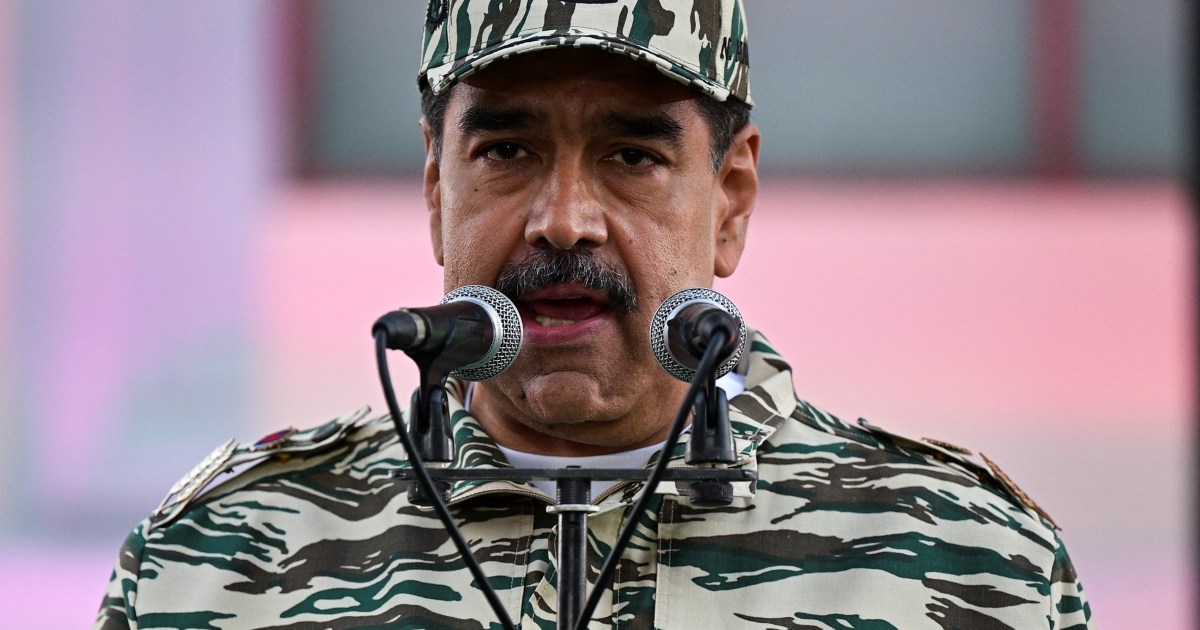

Venezuela’s Maduro says US nationals among group of ‘mercenaries’ detained

US transfers 11 Yemeni detainees from Guantanamo Bay prison to Oman

Hamas accuses Israel of delaying the implementation of Gaza ceasefire deal